Let’s continue the discussion about drug-device/delivery products.

In the previous post, I made the claim that you have to be best-in-class to have a venture scale outcome.

Starting with this post and continuing through a few more, I am going to deconstruct the elements that go into creating a product that has the highest chance of generating a venture scale outcome. We will do this by spending time on identifying routes that have led to great and suboptimal outcomes.

Why?

Because if you look at resources that describe how you should build a drug-device or delivery product, it would all sound very obvious - identify a clinical need, speak with patients/physicians, design, iterate and so on. I mean it is 2025, are we really starting companies without doing that?

What I have found missing is an in-depth scan of what seemed to be good ideas and turned out that way and which ones didn’t quite pan out that way. As I detail my thinking, I also want to explicitly state that my analysis relies on backward-looking data. Just because some routes have led to suboptimal outcomes, doesn’t mean they will continue to be that way. There will always be an exception that defies all prior frameworks and predictions! If that is you, I would be really happy! I provide this analysis so you can understand what perceptions you are up against and make your case accordingly.

In the absence of successful startups in all these cases I will talk about, I will use revenue accrued to these products as a proxy for a startup. If these product lines were startups, I hypothesise they would make for (at least) decent exits if not blockbuster ones.

With that, let’s get into it. The most important set of questions to answer is basically what problem do you want to solve, why and how?

Too simple, right? Let’s add more depth to it.

Do you understand the unmet need and disease burden extremely well, in the context of available current treatments and human factors that surround its use?

Some questions that help you explore this are -

What are specific efficacy/safety limitations of the current standard of care?

Do you have quantifiable morbidity/mortality rates, impact on daily functioning, and psychological well-being?

What are some specific patient complaints (e.g., route of administration, pain at injection site, frequency of infusions, lifestyle disruption)?

Now, once you have identified an unmet need,

How will you provide clinical benefit by your product?

Some questions that help you explore this are -

What are specific mechanisms by which safety is enhanced (e.g., reduced peak-to-trough fluctuations, fewer injection site reactions)?

How quantifiable are improvements in bioavailability, targeted delivery, or dosing precision?

What are specific clinical outcomes enabled by new route/frequency (e.g., reduced hospitalizations, improved symptom control)?

Can you generate compelling new PK/PD modeling or clinical data demonstrating the advantage of the combination?

As a founder, you might already be thinking about these. So, here’s the not-so-obvious parts, that I think are not given deserved importance.

What are some potential routes that can lead to suboptimal outcomes

Overestimation of unmet need: assuming patient dissatisfaction without robust data OR relying on theoretical benefits rather than clinical evidence.

Ignoring subtle but critical patient concerns: overlooking lifestyle disruptions or minor side effects that significantly impact QoL or stigma around product use

Lack of quantifiable improvement: failing to demonstrate a meaningful clinical advantage over existing therapies or failing to consider how the device will perform in everyday patient use.

Focusing on minor PK/PD changes: overemphasizing small improvements that don't translate to meaningful clinical outcomes.

Enough of claims, let's look at some case studies that prove them.

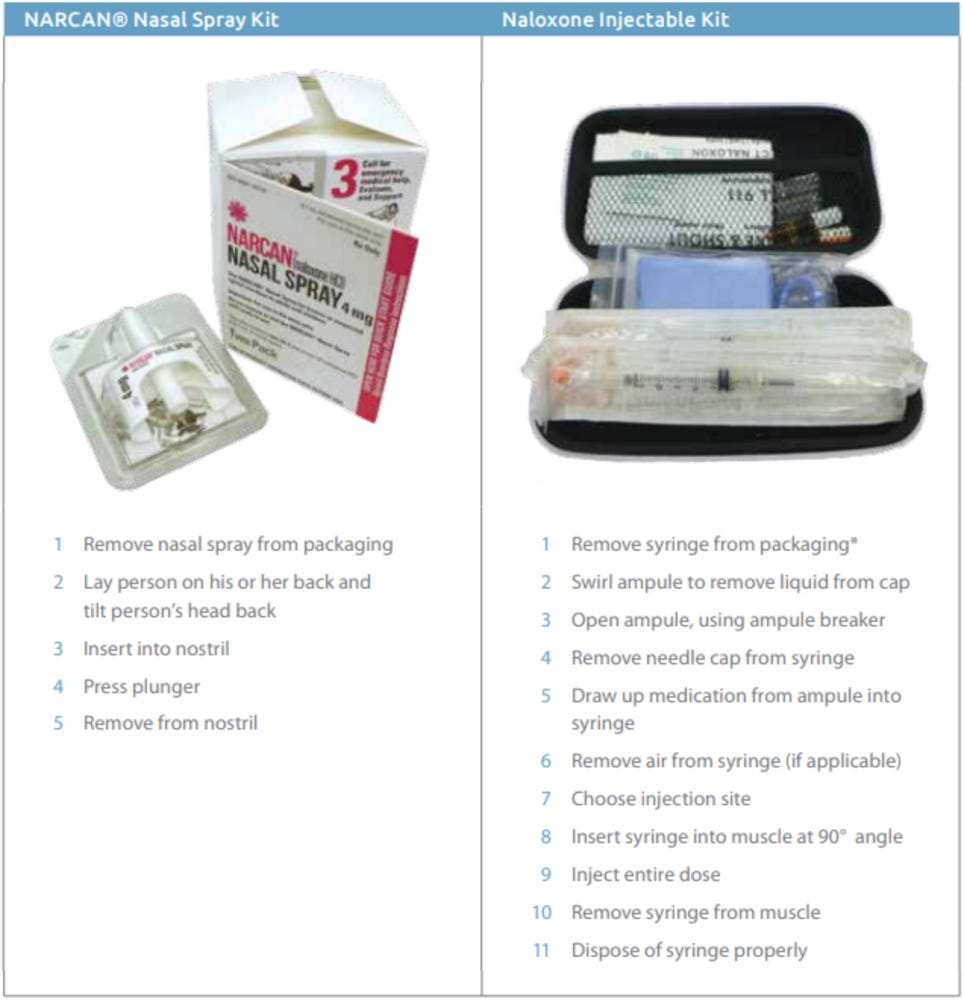

A. Narcan Nasal Spray

Unmet need: during opioid overdosing emergencies, you want the antidote (naloxone) intervention to act as fast as possible and that can ideally be administered by an unskilled bystander who might not be comfortable with injecting the person who is overdosing.

Solution: A nasal spray that would administer the same effective dose, reaching Tmax in minutes, without requiring any skill.

Result: the first year on the market, 2016, Narcan produced $24M in revenue. In 2024, it was $400M.

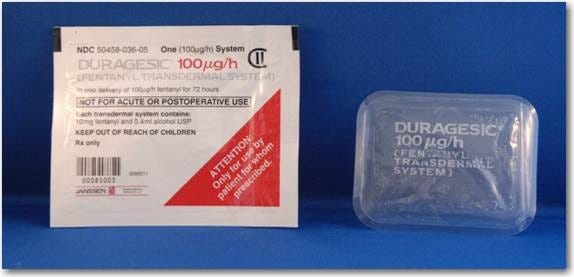

B. Duragesic

Unmet need: Patients with moderate to severe chronic pain (patients with cancer, arthritis, neuropathic pain, or who need end-of-life palliative care) needed an intervention that would provide sustained and steady delivery of the drug without having side effects of constipation, nausea and vomiting.

Solution: Duragesic delivers fentanyl at a steady rate through a skin patch designed for long-term use. After applying a patch, fentanyl is absorbed slowly – it often takes 12–24 hours to reach meaningful plasma levels and 24–72 hours to reach steady-state concentrations. Once steady state is achieved and as long as patches are replaced every 48–72 hours, blood levels remain relatively stable. Even after removing a Duragesic patch, fentanyl stored in the skin continues to enter the bloodstream for many hours (about a 17-hour half-life post-removal)

Result: As a pioneering long-acting opioid for chronic pain, Duragesic commanded a premium price when launched. Janssen’s brand Duragesic was a significant cost for chronic therapy, but payers generally covered it for appropriate patients (such as those with cancer pain or severe chronic pain) given the lack of alternatives providing similar around-the-clock relief. Duragesic had peak sales of $2.4B in 2004.

C. Abraxane

Unmet need: Paclitaxel, a potent anti-cancer drug made by BMS, traditionally required the solvent Cremophor for IV use, which caused hypersensitivity reactions and constrained dosing. The drug’s therapeutic window could be possibly widened by reducing the solvent-related toxicity due to Cremophor.

Solution: Abraxane, developed by Abraxis BioScience bound paclitaxel to 130nm albumin nanoparticles, creating a solvent-free colloidal formulation. This would improve drug delivery and distribution: the albumin nanoparticles better ferry paclitaxel to tumors (albumin can exploit tumor blood vessel permeability) and eliminate the need for toxic solvents. In terms of pharmacokinetics, Abraxane enables higher paclitaxel dosing with a shorter infusion, and without pre-medication (no steroid/antihistamine pre-treatments for Cremophor-related effects), because the formulation itself is more biocompatible.

Abraxane’s formulation delivered both improved efficacy and safety in clinical trials. In a Phase III trial in metastatic breast cancer, Abraxane showed higher tumor response rates and even improved overall survival (in second-line therapy) compared to conventional paclitaxel. The hypothesis was correct: patients benefited from the ability to receive higher doses of paclitaxel (since albumin-bound particles mitigate toxicity) – translating to better cancer control in some cases. The side effect profile was better: Abraxane avoids the Cremophor-related hypersensitivity and severe neuropathy, allowing 95% of patients to be treated without dose-reduction or heavy pre-medication.

The convenience of a 30-minute infusion (versus 3 hours for standard paclitaxel) and no need for IV corticosteroids meant less infusion clinic time and fewer adverse events for patients.

Result: Abraxane combined with gemcitabine became a standard option in breast, lung and pancreatic cancers. In 2010, Celgene acquired Abraxis for $2.9B.

Now, let's look at examples of products that didn’t get it right

A. Exubera

Unmet need: A needle-free insulin alternative with faster absorption than subcutaneous insulin would enable more diabetics to start insulin sooner. Additionally, the inhaled powder would reach peak insulin levels more quickly enabling more convenient mealtime dosing.

Reality: Inhaled insulin controlled blood sugar no better than injected rapid-acting insulin. Trials showed no improvement in HbA1c, hypoglycemia, or patient satisfaction versus standard insulin. One review said, “as effective, but no better” than injected insulin – any small PK difference had no added clinical benefit. There were even hints of higher severe hypoglycemia rates on Exubera. Moreover, the device’s use was critically impaired by the bulky, cumbersome inhaler and confusing dose conversions (milligrams instead of units).

Result: Physicians and patients largely rejected it, and insurers refused to cover its high cost given the lack of advantage. Pfizer saw dismal sales (only a few million dollars in its first year against expected billion) and withdrew Exubera in 2007.

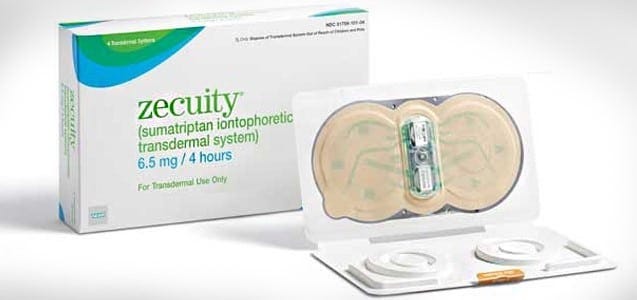

B. Zecuity

Unmet need: migraine patients desperately needed a better way to take medication during attacks, especially when experiencing nausea or vomiting.

Solution: The patch delivered sumatriptan (a migraine drug) through the skin via a mild electric current (iontophoresis), bypassing the GI tract.

Reality: the claimed unmet need was definitely overestimated. Non-oral options for migraines already existed (nasal sprays, injectable sumatriptan auto-injectors) and were reasonably effective. Many patients manage migraines with these options, and those with severe nausea often accept an injection if it works quickly. Zecuity, on the other hand, had a slow onset (about 2 hours for effect) similar to oral meds, diminishing its advantage. Worse, few months after launch, the patch caused unexpected side effects – the bulky battery-powered patch had to stay on for 4 hours and this prolonged wear sometimes led to burns and scars.

Result: Less than a year after launch, the product was pulled from the market by the maker, Teva.

C. Sumavel DosePro

Unmet need: Sumatriptan by injection has the fastest onset and highest efficacy among triptans (thanks to quick absorption and high peak levels). There would be wide acceptance of a product that allows you to treat migraines as rapidly as a traditional subcutaneous injection but without a needle.

Solution: Sumavel’s jet injector uses compressed gas to propel sumatriptan through the skin, aiming to provide the same rapid pain relief as a subcutaneous shot (“near-instant” drug delivery) while eliminating the fear and hassle of needles.

Reality: Trials confirmed the needle-free system was bioequivalent to needle injections. No superiority in pain reduction or consistency was demonstrated; it was simply an alternative route. For patients not averse to needles, Sumavel offered zero advantage over the existing 6 mg injection. Even for those with needle phobia, the benefit was limited – the device still caused a sting/bruising from the high-pressure burst and did not yield a better clinical outcome.

Result: Sumavel DosePro remained a niche product with low adoption. Some migraine specialists appreciated having a needle-free option, but most patients continued to use oral or nasal triptans for convenience, or conventional injections if they needed maximal speed. The device’s unique value (serving needle-phobic patients who require injection-speed relief) was real but too narrow to drive high volume. Zogenix, the original developer, never saw large sales and eventually sold the product rights to Endo in 2014. A few years later, Endo discontinued Sumavel entirely - the FDA announced its market withdrawal in 2018.

D. Diastat

(A prefilled syringe is just about barely a drug-device combination, but I bring this case in to discuss another important point: patient-centric design)

Unmet need: Patients with epilepsy can suffer breakthrough seizures that, if prolonged, may cause serious neurological damage or become life-threatening. Quick seizure termination, within minutes, is essential. Out-of-hospital management of severe seizures was very challenging because IV benzodiazepines were not accessible outside hospitals.

Solution: Diastat was developed as a rescue medication for epilepsy patients who experience prolonged or cluster seizures. It is primarily intended for use at home, school, or other out-of-hospital settings, providing rapid seizure termination when intravenous access isn’t feasible. It is pre-filled plastic applicator syringe - allowing caregivers or non-medical personnel to deliver a precise dose rapidly and safely, through the rectum. Rectal administration allows rapid absorption of diazepam directly into systemic circulation (avoiding the slower oral route and the complexity of IV administration). Diazepam achieves therapeutic blood levels typically within 5–15 minutes of administration. It has a half-life of approximately 20–50 hours, allowing sustained seizure suppression.

Reality: Initially, Diastat was widely adopted due to its clear unmet need, and it quickly became standard rescue therapy for severe seizures outside hospital settings. It was widely endorsed by neurology guidelines and epilepsy societies.

This is a classic case of design that was not patient-centric.

The rectal route led to poor patient and caregiver acceptance, limiting practical use despite clinical efficacy. Many patients or families would prefer waiting or risking an ER visit rather than using Diastat due to embarrassment or awkwardness associated with administration. Schools or other public settings often resisted using it or demanded extensive training, complicating its real-world utility.

Result: While Diastat did $75M in revenue in 2007, it has dropped since then to about $30M. Eventually, products like Valtoco (diazepam nasal spray, approved in 2020) were developed, providing effective seizure rescue without the invasive rectal route. These newer nasal spray formulations are rapidly becoming preferred treatments, improving both adherence and patient/caregiver acceptance.

Next, I will look at other often overlooked factors to consider in your ideation/creation process. What are they? More soon!

If you found this interesting, or you are building in the space, or you want to discuss something related, feel free to connect with me. I also welcome all feedback, so please drop them in the comments or DM!